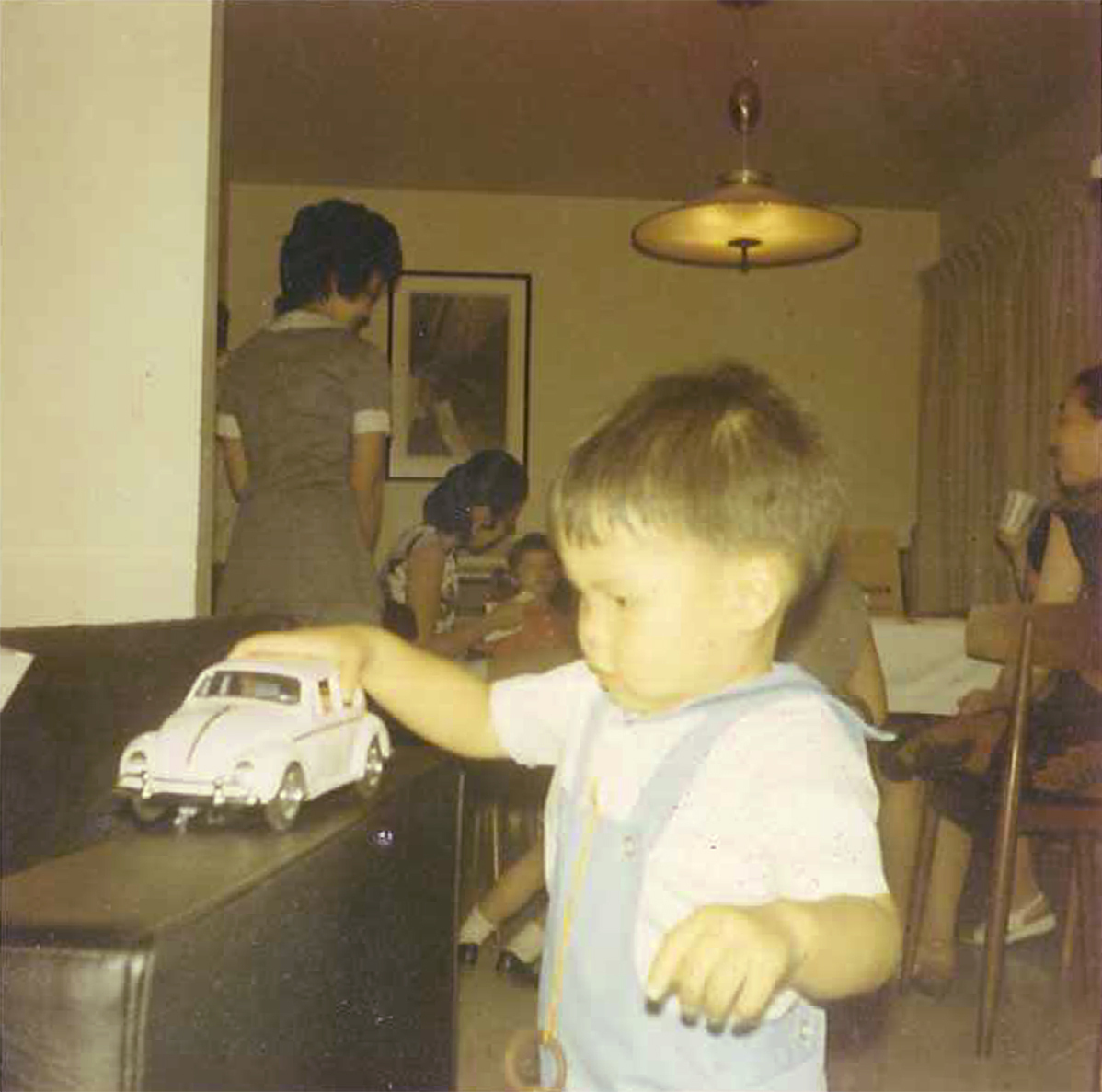

Kids play with toy cars like the Cozy Coupe partly because they want to imitate their parents: turn a steering wheel, open a door, strap a Christmas tree to the roof. But toy cars aren't just fun and games; they can suggest future trends in the automobile industry. Frank Guido/Flickr hide caption

toggle caption Frank Guido/Flickr Kids play with toy cars like the Cozy Coupe partly because they want to imitate their parents: turn a steering wheel, open a door, strap a Christmas tree to the roof. But toy cars aren't just fun and games; they can suggest future trends in the automobile industry.

Frank Guido/Flickr Morning Edition has reported that the Toyota Camry is the best-selling car in the U.S., and the Ford Focus is the world's best-seller.

Now it's time for a correction of sorts because it turns out the dominance of the Focus and Camry is rivaled by another car. It's American-made, has zero emissions and is highly affordable. We're talking about the Cozy Coupe — the yellow-roofed, red-bodied, kid-sized toy car.

Toys like the Cozy Coupe are more than just child's play. In fact, if you want to find out about the future of the auto industry, there's no better place to start than at a playground — like the one at California's Culver City Montessori School, where Cozy Coupes are one of the most popular toys.

Culver City Montessori teacher Micah Card explains that wanting to be "like Mommy and Daddy," as one child puts it, is a major part of a toy automobile's appeal.

"They really enjoy the Cozy Coupe cars because ... it has a roof, it has a door to open, it even has [a] little gas nozzle. They'll fight over those cars," Card says. "They don't really care so much for the open-top type ... because it's not as close an approximation to what their family drives. You know, they want to do what their parents do."

Do Cars Mean Freedom, Or Pollution?

Children become aware of cars, buses, trucks and planes — and the toys based on them — very early on. Richard Gottlieb, who makes a living analyzing trends in the toy industry, says playing with cars is fundamental.

"When they do these archaeological digs from Egypt or Rome they'll find little horse and chariots," he says. "They're primitive ... [the kind] that kids play with. So I think the desire to roll things has always been there."

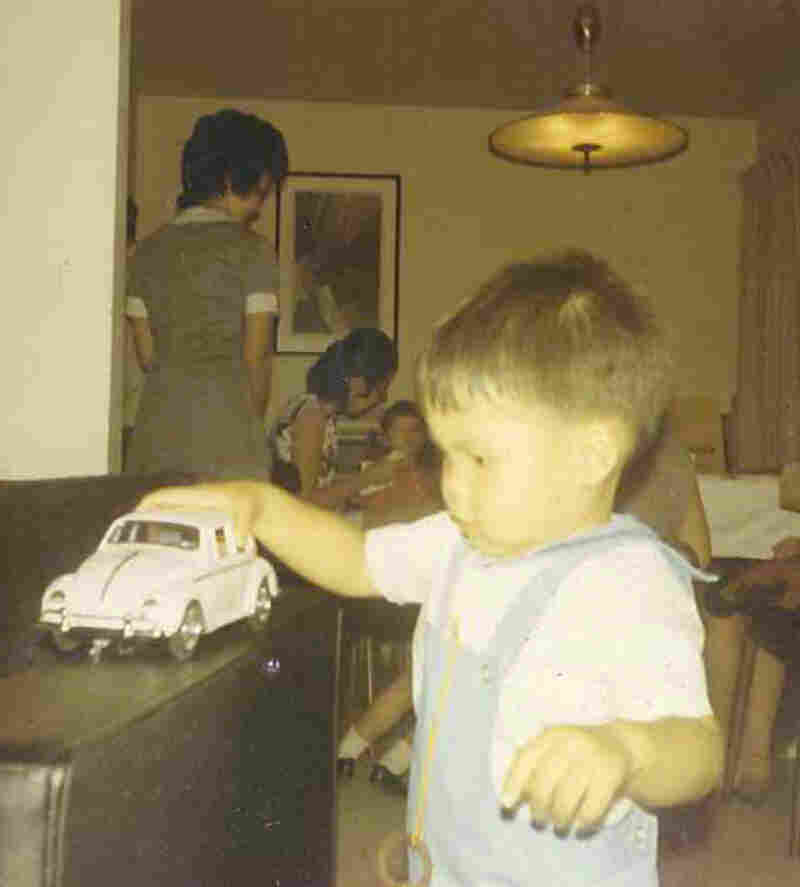

Mark Takahashi is now one of the "car people" at Edmunds.com — but at the age of 2, the future automotive editor, like his co-worker Mike MaGrath, was more of a toy-car person. Courtesy Mark Takahashi hide caption

toggle caption Courtesy Mark Takahashi Mark Takahashi is now one of the "car people" at Edmunds.com — but at the age of 2, the future automotive editor, like his co-worker Mike MaGrath, was more of a toy-car person.

Courtesy Mark Takahashi Gottlieb says the eagerness to play with cars hasn't changed but what kids think about those cars has.

"From an aspirational sense, I don't think children aspire to drive as much as they used to," Gottlieb says. "I think they aspire to have a cellphone, but not necessarily a car."

Indeed, driving as a rite of passage has diminished greatly in recent years. For some, cars still mean freedom, speed and escape; for others they mean isolation, gridlock and pollution.

Gottlieb says kids pick up on that, which is why you see more and more cars that have faces and stories, as in Pixar's Cars movies.

"If you really think about it, the children are engaging the characters; they're not engaging the brands," Gottlieb explains. "Maybe not great news for the car companies, but I think that probably signals some of the loss of prestige for driving among youth."

The declining appeal of the automobile might not be good news for toy companies either. Kids' love for cars used to drive a passion for their toys; at least that's how it worked for Mike Magrath.

Today, Magrath is an editor at Edmunds.com, an online source of automotive information. At the office building where he works, nearly every single one of his co-workers has toy cars strewn across his or her desk. Magrath can still remember the first car he fell in love with.

"Mine was probably a pedal car. It wasn't a toy car per se, like a Matchbox or a Hot Wheels, but I remember this small, I think it was rocket-ship designed — it had pedals, and you could run it with your feet."

"I would always try to go just as fast as I can down through the kitchen and down the stairs. It's all I wanted ... because I thought if I hit those stairs fast enough, I would just leave the house," he remembers. "It just ended up with my mom installing a safety gate. But I loved that toy."

Magrath didn't know at that age that he wanted to work with cars.

"I just knew that cars sort of represented something I could play with, something that I could go out and have adventures in," he says. "And it never stopped."

Kids' Cars Go Green

The connection between the fantasy world of toy cars and their real-life counterparts is absolutely direct — a highway that moves in both directions, very fast. Car companies license their designs to toy companies, and toy companies reflect auto trends in their merchandise.

Felix Holst, left, is the head designer of Hot Wheels and Matchbox cars for Mattel. Holst demonstrates some of his team's designs to Aaron Schrank, center, and Sonari Glinton. Courtesy Kristin Hull hide caption

toggle caption Courtesy Kristin Hull Felix Holst, left, is the head designer of Hot Wheels and Matchbox cars for Mattel. Holst demonstrates some of his team's designs to Aaron Schrank, center, and Sonari Glinton.

Courtesy Kristin Hull At the intersection of those worlds is Felix Holst, the chief designer of Matchbox and Hot Wheels for Mattel, the toy conglomerate. He calls his home base in El Segundo, Calif., "the most wonderful place in the world."

Holst takes toy cars very seriously. He and his team design dozens of them a year, and they sell well over 6 million a week.

Holst's job is to listen to little boys and girls and give them (and their parents) what they want. What he's found is that the new generation of children — 3- to 6-years-olds — really cares about issues like green design.

"Six-year-olds are talking about green design in school. ... Six-year-olds are learning about energy conservation and recycling," he says. "They're learning about pollution. They're learning about gasoline engines vs. electric cars."

So Holst has been designing cars that signal to kids that they are fuel-efficient — that they represent something different than the experience their parents are having right now. He says car designers have to learn a new visual language to make cars attractive for modern children.

"What we're finding ... for kids is that driving is not — it's not an appetizing prospect," Holst says. "It's very difficult. It's very costly. It's dangerous. ... They're more connected now than they ever were before."

Selling Toys, Creating Customers

The companies that Mattel contracts with — that is, all the major automakers — increasingly have to talk that language to kids as well. Ford's Patrick Mulligan says companies like his go to great lengths to make an impression on kids through licensing deals.

"When a company makes a toy of a Mustang, and it's going to have an engine sound, we make sure that that engine sound sounds like a Mustang," he says.

Kids can tell the difference, Mulligan explains.

"They know a Ford from a Chevrolet from a Dodge from a Toyota, and they have their favorite," he says.

Before Mulligan was in the car business, he was in the toy business. He says that because today's children are less interested in brands, it's not enough to just get kids to know a Ford from a Chevy. He wants kids to know what Ford is about.

"It's things like figuring out ways to integrate SYNC ... into a toy so that children see how Ford is a company that's at the leading edge of technology," he explains.

Car companies are hoping that if they can interest these kids in driving now, they'll be drivers in the future — and that when they trade in those Cozy Coupes for highway-ready vehicles, they might be choosing between brands they recognize from their toy boxes.